Tags

Carolingian Empire, Charlemagne, christendom, Holy Roman Empire, J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, The West

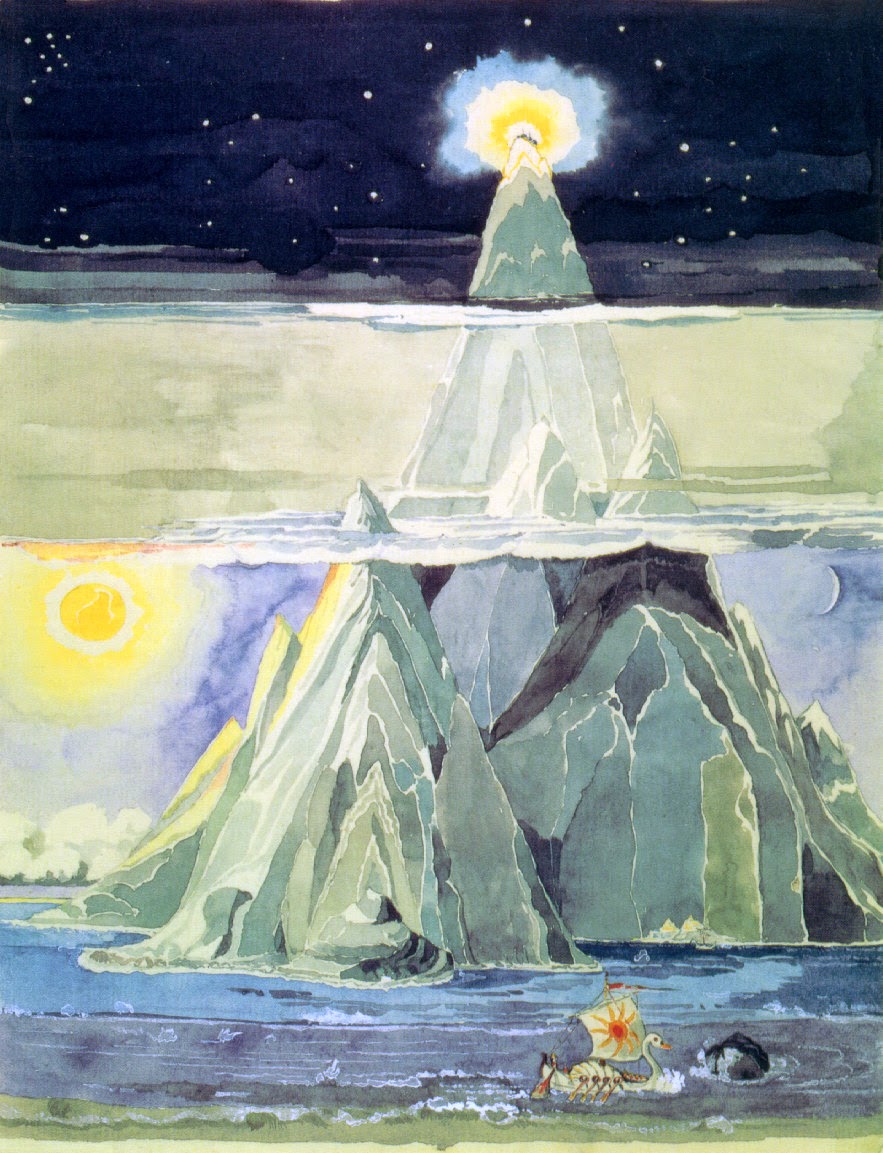

Upreared from sea to cloud then sheer

a shoreless mountain stood;

its sides were black from the sullen tide

up to its smoking hood,

but its spire was lit with a living fire

that ever rose and fell:

tall as a column in High Heaven’s hall,

its roots were deep as Hell;

grounded in chasms the waters drowned

and swallowed long ago

it stands, I guess, on the foundered land

where the kings of kings lie low

-J. R.R. Tolkien, Imram (The Death of St. Brendan)

Each of the subcreative works of J.R.R. Tolkien displays a careful and thoughtful attention to the cultures and civilizations which populate his secondary reality. He drew deep and rich realities from the history of the Primary World and studying his invented histories can illuminate both philosophical and macro-historical themes with which Tolkien engaged. In particular, investigating Tolkien’s use of the West as a civilizational concept in his novel The Lord of the Rings, written between 1937 and 1954, reveals his appropriation of the Carolingian heritage of Europe, which transformed the work from what was originally intended as a “mythology for England” into what Bradley Birzer calls “a myth for the restoration of Christendom itself.” This appropriation was controversial, especially during the Second World War when the National Socialists in Germany attempted to usurp this European heritage for themselves. A close reading of The Lord of the Rings reveals the parallels between Tolkien’s restored Kingdom of the West and the Carolingian Holy Empire, the West as a source of spiritual renewal, and Tolkien’s defense of Western mythology against the Nazi usurpation of the European tradition.

In the intricate web of plotlines and characters which comprise The Lord of the Rings, the story of Aragorn Elessar and his restoration to the thrones of Arnor and Gondor bears the strongest imprint of Carolingian history. Aragorn is described at the conclusion of his story as “the King of the West,” the first king to rule over all the Western lands since his ancient ancestor Elendil perished in the war against Sauron. Like Charlemagne, who as Emperor of a revived Western Empire is said to have received homage from Irish and Spanish Kings, Aragorn takes the free peoples of Middle-earth “under the crown and protection of the King of the West. These parallels are not superficial but were directly acknowledged by the author himself. Writing in response to claims that his novel represented a Nordicist spirit, Tolkien explained that “the progress of the tale ends in what is far more like the re-establishment of an effective Holy Roman Empire with its seat in Rome.” Here Tolkien invokes the cultural restoration of Western Europe undertaken by Charlemagne after he was proclaimed emperor. The correspondence between Aragorn’s reign and Charlemagne’s renovatio imperii Romani is most evident in the descriptions of their respective coronations. Tolkien’s fictional coronation of Aragorn is, as Birzer writes, medieval in form:

Then Faramir stood up and spoke in a clear voice: “Men of Gondor, hear now the Steward of this Realm! Behold! one has come to claim the kingship at last. Here is Aragorn son of Arathorn, chieftain of the Dúnedain of Arnor, Captain of the Host of the West, bearer of the Star of the North, wielder of the Sword Reforged, victorious in battle, whose hands bring healing, the Elfstone, Elessar of the line of Valandil, Isildur’s son, Elendil’s son of Númenor. Shall he be king and enter into the City and dwell there?

And all the host and all the people cried yea with one voice. . . . Then Frodo came forward and took the crown from Faramir and bore it to Gandalf; and Aragorn knelt, and Gandalf set the White Crown upon his head and said: “Now come the days of the King, and may they be blessed while the thrones of the Valar endure!”

This description of the coronation ceremony intentionally mirrors the Papal coronation of Charlemagne on Christmas day in A.D. 800, as described in The Annals of the Franks:

And that very same day, when the king rose from prayer before the confession of St. Peter, Pope Leo placed a crown on his head and he was acclaimed by the whole people of the Romans: “To Charles augustus, the God-crowned great and pacific emperor of the Romans, life and victory!” And after the acclamations, he was saluted by the pope in the customary manner of ancient emperors, and the name of patricius was abandoned and he was called emperor and augustus.

After their coronations, both rulers exercise the ruling virtues of justice and mercy. As Aragorn judges the former allies of Sauron with lenience, Charlemagne shows mercy to the enemies of the Pope at his behest, sparing them the mutilation that was required by Roman law and granting them exile instead. Both accessions to power rely not only on the acclamation of the populace but also on the approval and benediction granted by spiritual authorities. As Charlemagne modeled his rule on St. Augustine’s City of God, Tolkien in turn models Aragorn on Augustine’s “characterization of the Christian Emperor.” Their reigns are contingent upon their exercise of the rule of virtues. In drawing upon the Carolingian tradition of the transference of power through priestly mediation of Divine Providence, Tolkien is reminding his readers of a vision of authority beyond the mere democratic sovereignty invoked by his contemporaries. It harkens back to a hierarchical yet free vision of society in which the state is accountable not only to the masses but even more immanently to the Creator of the World.

Yet Aragorn’s rule is no mere allegory for the reign of Charlemagne. Rather, Tolkien integrates both elements of the life of the historical Charlemagne and the mythological figure of the “Last World Emperor” from medieval Europe into his legendarium. Joshua Hren writes how Tolkien joined “a long line of Catholics given to anticipating the Return of a King,” when he compared the reestablishment of the Kingdoms of Arnor and Gondor to that of the Holy Roman Empire. Aragorn’s rule, like that of the mythical “Emperor,” is prophetically foretold, foreshadowed by his miraculous healing abilities. Thomas W. Smith makes this parallel more explicit when he writes that Aragorn “spends most of his formative years in the wilderness. . . protecting its vestiges in the hinterlands of the old empire of the Númenoreans.” Charlemagne was brought up in palaces as the heir to a powerful king; his ultimate successor, much like Aragorn, was to arise from among the dispossessed, echoing Christ’s humble birth in a stable. Aragorn’s journey mirrors “in a mythological sense,” the popular prophecy of restoration, whereby “Christendom has united been united, and its enemies isolated and dealt with.” Aragorn, like the “Last World Emperor,” becomes an implicitly Christ-like figure, as Tolkien uses his novel to anticipate “the fulfillment of so many Catholic prophecies in The Return of the King.” Within its fantastical setting, the story serves as a mythological visualization of the future history of Christendom as it existed in the Medieval imagination.

But perhaps the deepest and most enduring legacy of the Carolingian world in Tolkien’s work is his vision of the West as a source of spiritual regeneration. While the political geography of Tolkien’s work most closely matches the medieval European self-understanding of a Catholic continent under siege, his spiritual geography more closely resembles that of the medieval Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis. Both texts use the cardinal location of the West as a symbol for the very real yet invisible spiritual world. Though not as pronounced as in his prior mythological writings, Tolkien uses the West in The Lord of the Rings to express immaterial spiritual values. When Faramir’s men in Ithilien, following the general custom of Gondor, make a kind of grace before their meal, they “turned and faced west in a moment of silence.” Faramir explains to Frodo that they “look towards Númenor that was, and beyond to Elvenhome that is, and to that which is beyond Elvenhome and will ever be,” thus expressing a physical and spiritual continuity between the past, the present, and eternity. Sam, almost subconsciously, invokes the West for supernatural aid when in the depths of the misery of Mordor he sings, “In western lands beneath the Sun / the flowers may rise in Spring.” The “Free Peoples of the West” around whom the novel is centered are also defined in such a way that their geographical location in the West of Middle-earth is related to their spiritual rejection of the Ring and its empty promises, echoing the self-identification of Western Christendom with the Roman Church. But the strongest link with the medieval vision of the Navigatio is Elvenhome itself, Valinor the undying isle.

In this ninth-century retelling of his life, St. Brendan seeks in the West “the Land of Promise of the Saints, a green and fruitful country where it is always light and the very stones beneath one’s feet are precious.’” This description bears a striking resemblance to the description given by Tolkien of the approach in Valinor in the final chapter of his work:

And the ship went out into the High Sea and passed on into the West, until at last on a night of rain Frodo smelled a sweet fragrance on the air and heard the sound of singing that came over the water. And then it seemed to him that as in his dream in the house of Bombadil, the grey rain-curtain turned all to silver glass and was rolled back, and he beheld white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise.

The similarity between the Western Paradise of St. Brendan and the Western land to which Frodo is sent for healing should not be surprising, as Tolkien was intimately familiar with those very same medieval legends. Around the same time during which he was engaged with the writing of The Lord of the Rings, he composed a poem dedicated to the final voyage undertaken by the Irish saint-voyager entitled Imram: The Death of St. Brendan. While references to an earthly paradise forbidden to mortals long predate the Christianization of Europe, the explicit placement of this paradise in the West carries with it Christian connotations of the Second Coming of Christ and the final twilight of the fallen world of sin. This conception of the earthly Paradise spread throughout Europe in works such as Navigatio, and continued to have a strong impact on the imagination of Christendom even during the Early Modern discovery of the New World. These references to Valinor and Elvenhome located in the West are a continuation of Tolkien’s mythologization of medieval Christendom.

To understand Tolkien’s incorporation of the Carolingian ideas of Empire and the Western Paradise one must place them in the context of his broader fight against the National Socialist appropriation of European mythology. As historian Christine Chism writes, “National Socialist Germany had made myth-production into a political strategy.” Like Tolkien, Hitler and other Nazi leaders attempted to use the mythological status of Charlemagne to bolster their own narrative of the future of Europe, praising him as a representation of Hegel’s world-historical spirit. They saw it as their mission to rectify Charlemagne’s “failure” by completing “his work of the subjection of the East” and indeed the entire continent to their own direct rule. But there is absolutely no resemblance between the Hegelian “Great Man of History” invoked by Hitler and the Christ-like ruler who forms the model for Tolkien’s Aragorn. In his letters written during the Second World War, Tolkien accuses the Nazis of “ruining, perverting, misapplying, and making forever accursed” pagan Nordic mythology, and he took very much the same approach towards their appropriation of Europe’s explicitly Christian history. He joined to the war against Hitler a “burning private grudge . . . against that ruddy little ignoramus.” “Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings,” Chism declares, “is thus not an allegory or a reflection of the war, but a responsive defiance” against the Nazi usurpation of mythology. His work “strategizes against the impact of the National Socialist corruption of mythology, its state conscription of aesthetics, its deft manipulation of sublimity” by grounding itself in genuinely medieval conceptions of the history of Christendom. Hitler idealized Charlemagne as a warlord and a conqueror; Tolkien on the other hand, portrays Aragorn first and foremost as a healer, a worker of miracles that bring wholeness and restoration: “the hands of the king are the hands of a healer.” As Hren points out, this medieval vision of the king as healer extends even to the “healing of the land itself,” an ideal utterly at odds with the mass destruction of both peoples and lands wrought by the Nazi regime during the Second World War. Nor is this healing confined to a single land; a nationalist or imperialist conception of power is explicitly rejected when Aragorn takes up the leadership of the entirety of the West. Instead, by embracing the Carolingian ideal of Christendom in a mythological form, Tolkien brings together a multitude of peoples, each retaining their own particular characteristics and freedoms, in the unity of a good purpose under a common authority.

It is a serious error to mistake Tolkien’s mythologization of the West and his intense opposition to National Socialism as a sign of unwavering support for the Western Allies. He lamented the fact the war was being waged as the “first War of the Machines,” and compared his son’s service in the RAF to “Hobbits learning to ride Nazgûl-birds, for the liberation of the Shire.” His continual references to the “long defeat” show a considerable disillusionment with the post-war order technocratic order. But the most telling sign of his disappointment with the Allied forces in the Second World War comes in the Foreword to the second edition of The Lord of the Rings in which he writes:

The real war does not resemble the legendary war in its process or is conclusion. If it had inspired or directed the development of the legend, then certainly the Ring would have been seized and used against Sauron; he would not have been annihilated but enslaved, and Barad-dûr would not have been destroyed but occupied. Saruman, failing to get possession of the Ring, would in the confusion and treacheries of the time have found in Mordor the missing links in his own research into Ring-lore, and before long he would have made a Great Ring of his own with which to challenge the self-styled Ruler of Middle-earth.

That Tolkien believed that the Allies would have seized and used the Ring- indeed, that they in fact did use the Ring- shows his lack of confidence in their ability to conform to the ideal of Christian rule. This damning indictment of the Allied powers reinforces the claim that Tolkien is not simply allegorizing modern history; rather he weaves medieval history and prophecy together in the creation of a myth for the return of Christendom.

There are many other ways in which Tolkien’s use of the West as a sacred and typological space could be explored. Rather than summarizing all of these different approaches, I have sought to engage in a rather direct examination of the influence of a particular medieval conception of the West on Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and placed it in dialogue with the most formative event in Tolkien’s lifetime. From the vision of Christian rule which Tolkien inherited from the Carolingian Empire, to his appropriation of a distinctly Catholic medieval prophecy, and his use of the West as both a political-geographic and spiritual reality, Tolkien’s Middle-earth reflects back to us a uniquely Catholic mythology. He combined these elements to place The Lord of the Rings in direct defiance not only of the National Socialists and their corruption of mythology but also of the post-war technocratic order with its emphasis on the domination of the machine. In so doing, Tolkien joined the ranks of the numerous Catholic critics of modernity who envisioned a return to the medieval unity of Christendom as the only path of salvation open to the modern West.

For Further Reading:

Birzer, Bradley. J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle-earth.

Chism, Christine. “Middle-earth, the Middle Ages, and the Aryan Nation: Myth and history in World War II.” In Tolkien the Medievalist. Edited Jane Chance.

Hren, Joshua. Middle-earth and the Return of the Common Good: J.R.R. Tolkien and Political Philosophy.

Nelson, Janet L. King and Emperor: A New Life of Charlemagne.

Roche, Norma. “Sailing West: Tolkien, the Saint Brendan Story, and the Idea of Paradise in the West.” Mythlore 17, no. 4 (Summer 1991).

Smith, Thomas W. “Tolkien’s Catholic Imagination: Mediation and Tradition.” Religion & Literature 38, no. 2 (Summer, 2006).