Tags

Age of Discovery, Book Review, Charles V, christendom, Holy Roman Emperor, Holy Roman Empire, Kingdom of Spain, New World, Otto von Habsburg

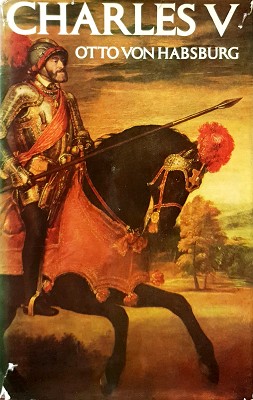

Otto von Habsburg, Charles V, trans. Michael Ross (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1970)

Born on the eve of the cultural and political upheaval of the sixteenth century, Charles V inherited a vast and wide-reigning authority as King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor that few men in history have ever rivaled. Dr. Otto von Habsburg, a descendant of Charles and heir of the last Habsburg emperor, prefaces his renowned ancestor’s 1967 biography by stating “later centuries were incapable of grasping Charles V’s conception of the world.” Nevertheless, Habsburg argues that challenges facing Europe in the present day are similar enough to the cultural revolution of the sixteenth century that “Charles V, once regarded as the last fighter in a rearguard action, is suddenly seen to have a been a forerunner.” Throughout the book he explores the relevance of the deeply Catholic and chivalric vision of Christendom that motivated Charles’ reign. It might seem easy to accuse the author of a favorable bias towards his subject, an accusation from which the book is not entirely immune. However, such an accusation ignores the real awareness of Charles’s vision that Habsburg gains from his concrete understanding of his own familial tradition. Otto von Habsburg’s Charles V offers a brilliant insight into the world and worldview of the history-shaping emperor, yet its lack of primary source citations and heavy reliance on secondary sources render it more of an introduction to its subject, and not, as seems to have been intended, an analytic biography.

The focal point of Habsburg’s Charles V is Charles’ vision as a ruler and how that vision was consistently acted upon in the rapidly changing world of sixteenth-century Europe. Contrary to the political philosophy of Machiavelli prevalent among rulers of that era, Habsburg confidently states that Charles “saw the state, politics, and war through the eyes of a knight, an emperor, and a Christian”. While these ideals seem in some way bound to the Middle Ages and out of place in the modern world, Habsburg maintains that the emperor’s “conception corresponds to the fundamental principles rooted in human nature,” principles which are relevant to any age. Thus, the central argument of the biography is to show how these principles, identified as honor, justice, and devotion to the Catholic faith, were practiced and upheld by Charles throughout his life. More than simply a figure of historical interest, Charles is presented as an exemplar for modern political leaders, especially those seeking a supranational European unity as the solution to the crises of the twentieth century.

Roughly chronological in its structure, Charles V presents its threefold focus on knighthood, emperorship, and piety as thematically tied to all major stages of Charles’ life. Focus in the first chapters is given to the significance of the Habsburg patrimony, specifically the Burgundian inheritance and its focus on supranational chivalry represented in the Order of the Golden Fleece. The description of Charles’ childhood education by Guillaume de Croy at court in Ghent from A.D. 1500-1515 and contemporary political developments in Spain are used to highlight the formation of his worldview, his guiding vision for his globe-spanning Imperium. In the middle chapters specifically relating to Charles’ reign in the Holy Roman Empire from 1519 onwards and the crisis caused by the Italian Wars that spanned half the century, Habsburg shows how this worldview guided the emperor’s actions in practical terms. His campaign in Tunisia is introduced as the culmination of the Crusading tradition of Burgundy, echoing Burgundian heroes Charlemagne and Godfrey de Bouillon. The religious conflict caused by Protestantism and Charles’ insistence on upholding the Catholic faith through his constant calls for an Ecumenical Council to confront the growing heresy are discussed simultaneously with the political revolt of the Imperial Princes and the Schmalkalden War of 1546. A chapter covers the much-neglected policies of Charles V towards his new world possessions, emphasizing the sovereignty he allowed them “as ‘republics’ governed by viceroys,” and the seriousness with which he carried out his desire to grant the native populations both the Catholic faith and the freedom of the rights of his European subjects. After his abdication in 1556, the piety which had guided his religious policies is shown in a more personal aspect during his retirement at the Convent of Yuste. The biography ends with an analysis of the emperor’s personality and an evaluation of his historical legacy, both as it was presented by nationalist (and often Protestant) historians in the past and as it has been reexamined by more neutral scholars in recent times. Habsburg does not shy away from his ancestor’s failures: his inability to fully address the exploitation of American Natives, his frequent procrastination, or his overly lenient compromise with the Protestant German princes. Indeed, he highlights the failure to accomplish the goal of lasting European peace by quoting historian Karl Burckhardt, “The balance sheet which Charles might have drawn up on his death bed. . . must surely have been summed up in the words: in vain.” The last word, however, is given to the transcendent ideal which carried Charles through all his successes and failures, his “unshakable faith and confidence in God’s wisdom.”

Throughout its chapters, Habsburg’s Charles V displays a rich understanding of contemporary worldviews presented in a well-constructed narrative. Burgundian chivalry with its high medieval code of honor, the foundation of such diplomatic actions as the Treaty of Milan in 1526, is described in vivid and understandable terms. When he writes how Charles’ “Burgundian spirit and personal sense of honour made him shrink from the idea of taking advantage of the weakness of an enemy,” it is understandable that Charles would disdain such an advantage because of the concrete descriptions given to the cultural milieu which formed him. Exploring the theme of emperorship, he outlines the essential division between the old ideals of the Crown of Charlemagne, and the still embryonic nation-state. He uses Charles’ own words to define the role of the Emperor “to ensure the peace of Christendom. . . for the greater glory of the Christian faith.” Charles’ vision of universal Empire as a form of ensuring the justice and unity in Christendom is directly contrasted with the policies, not only of his enemies, but even of such loyal supporters as Hernan Cortes, whom Habsburg describes as seemingly “the incarnation of all the theories of his contemporary, Machiavelli.” Charles devotion to Catholic orthodoxy is equally well contrasted with the religious fervor of Martin Luther, who is credited for being “undoubtedly the most remarkable” of Charles’ contemporaries. His personal self-control, courage, and respect for justice are shown to derive directly from “his allegiance to God and the Christian faith.” Though covering a broad and everchanging period of history, the narrative is written in consistent and well-structured prose, which does not lose its crispness in its translation from the original French.

Unfortunately, the arguments presented are often lacking in relevant primary source citations. Backed by an extensive bibliography, the use of quotes contemporary to the subject is nonetheless minimal. Habsburg instead prefers to present the research of later historians, primarily Leopold von Ranke and Karl Burckhardt. This approach has some benefits, such as a more concise retrospective description of key events, but is ultimately weaker in its arguments than a biography which conducted an in-depth analysis of period sources. Such use of quotations would also contribute much to a refutation of claims that the book is solely a hagiographical account motivated by Habsburg’s own nostalgia. While a close reading of the book very clearly manifests the quality of his research, his much shallower exploration of contemporary figures’ opinions regarding Charles’s actions, and of Charles’ own personal failures and struggles, does give some credence to this idea. To a certain extent the focus on the ideals and worldview of Charles the emperor, which are the biography’s great strength, are also its latent weakness, preventing it from giving a wholly realistic portrait of Charles the man.

Charles V is a fascinating biography both for its understanding of the ideals and worldview of Emperor and King Charles V, and for its insight into the living legacy with which Charles imbued the Habsburg tradition. Throughout the book the impact of Charles’ vision can be seen in Otto von Habsburg’s own principles formed by his imperial heritage. Writing at a time when the Burgundian homeland of Charles was becoming “the key piece in the plans for a European entente,” Habsburg is fully committed to the ideal of supranational unity that earlier nationalist historians found so difficult to comprehend. From this knowledge of his ancestor’s goals, sense of honor, and devotion to his faith, Habsburg is able to correct several misconceptions promulgated by these authors. Despite not being deeply analytical of contemporary sources and of Charles’ own personal character, Charles V is nevertheless a well-crafted introduction to the emperor, his vision of Western Christendom, and how he has inspired his descendants to maintain this vision, even to the present day.